Financing abolition

The debate about the appropriate way to handle the 19th century compensation of slave-owners is likely to rumble on for a while, so I thought it would be useful to put together a quick post pulling together the main facts in the debate: how much was paid to end slavery, when it was paid, who it was paid by, why it was paid, and some of the consequences of these payments.

One of the first things brought up in this sort of conversation is that Britain didn’t finish paying off the debt from compensating slave-owners until 2015. This is one of those things that’s based in truth but abstracts away from quite a lot of complexity.

The money that financed the abolition of slavery was initially borrowed in 1835 (1). These bonds sat in the national debt until 1927, when the government decided to refinance. This process involved buying out old bonds and issuing new ones, which were undated. An undated bond is pretty much what it sounds like: the government makes an interest payment each year until it decides to pay back the sum borrowed (redeem the debt), but has no obligation to actually redeem it on any particular date.

How many of the new bonds were related to debt from the abolition of slavery is a total mystery. When the debt was refinanced, bond owners could choose to redeem bonds rather than convert them, and these decisions weren’t recorded. How much we were paying for the abolition of slavery in 2014 is unknown.

We can however be pretty sure that we weren’t still compensating the descendants of slave-owners. This is partly because bonds can be bought and sold and 180 years is a long time, but mostly because the interest payments on the debt by definition were made (originally) to the people who lent the sum rather than the people who received it. In other words, we would have been paying the descendents of the people who funded abolition (2).

The long duration of repayment wasn’t because the sums involved were so vast. The government didn’t pay off these bonds until 2015 because it wasn’t worth doing. From a net present value standpoint, the payments on these bonds were low relative to current interest rates. When that changed, the government redeemed the bonds, financing this as part of the usual debt sales programme (3).

It’s worth digging into this a little because it’s often used as a rhetorical device in arguments about the degree to which British wealth rests upon slavery (see my Spectator article for a general rebuttal), and in calls for reparations. Understanding the actual numbers involved is useful for keeping these debates grounded in a degree of reality.

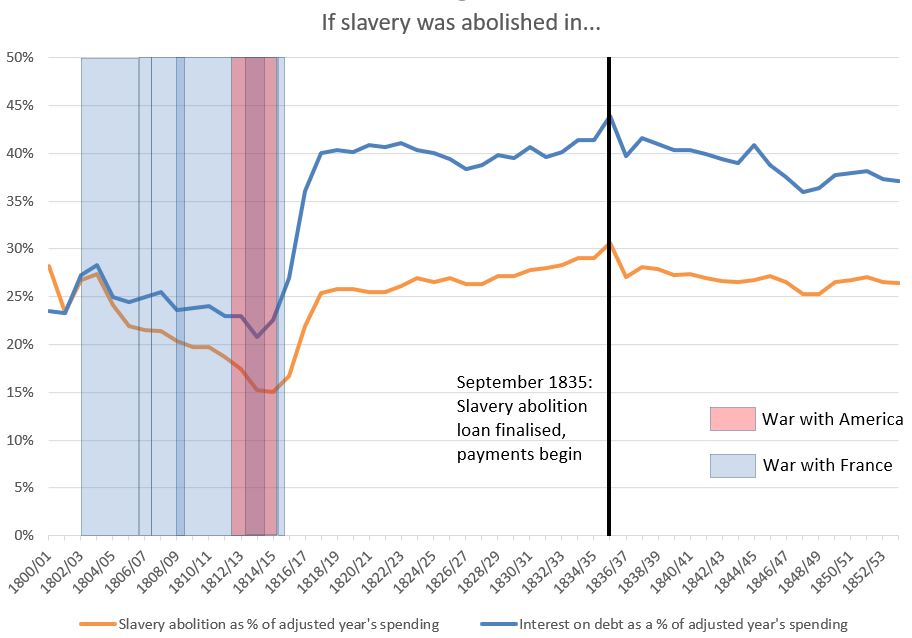

There are two sets of numbers usually used to explain why the debt took so long to pay off. The first is the share of the government budget, generally stated that the bill for abolition came to 40% of government spending in 1833. As far as I can tell this is a misconception; the abolition act was passed in 1833, but the loan organised by Nathaniel Rothschild and Moses Montefiore which financed the compensation of slave-owners wasn’t finalised until 1835, with payments beginning in September of that year. In that year, £20 million is equivalent to ~30% of the budget.

It’s also important to understand what this meant in practical terms. At that point in history, the purpose of the budget was to either fund your latest war against France, or pay off the debts from the last one. When you aren’t spending much, any lump sum is a larger share of the total (4).

The graph below shows what proportion of government spending abolition (valued at an addition of £20 million to that year’s spend) would have constituted in each year from 1800 to January of 1854, compared with spending on servicing the government debt. (5).

In cash terms, the sums sound quite large. Prices are ~100 times higher now than they were then, so £20 million in 1835 is worth about £2.5 billion today. Unsurprisingly, people receiving this money invested it and a number of businesses can trace back a line to at least some of the compensation bill. Describing this as a transfer of wealth from the Caribbean to Britain as some have done is a misconception; this was the use of funds raised inside the United Kingdom to effectively buy the liberty of slaves overseas, an internal reallocation rather than an extraction from one region to another. In turn, arguing that compensation payments were a way in which slavery contributed to development is also based on a misunderstanding. Public debt was raised to make these payments, squeezing out other economic activity (6).

Another figure used from time to time is £20 billion. The earliest variant of this figure I can find is a 2013 reference to a UCL study reaching £16.5 billion, and this includes the interesting term ‘wage values’. If you inflate this figure with the Bank of England’s Composite Average Weekly Earnings series, you’ll reach figures of a similar size.

The problem with this is it’s not really the correct concept. The idea of adjusting for inflation is to give a sum in terms of a constant amount of spending power; £20 million in 1835 buys you £2.5 billion worth of goods today. If you adjust for wages, you’re building in productivity growth. You’re asking something closer to “what would the amount of work needed to earn £20 million in 1835 earn today”, which isn’t quite as useful (7).

Regardless, £2 billion is a lot of money. It’s still a number that needs some context; it’s equivalent to 0.3% of government spending this year, or somewhere in the region of 4% of the final cost of High Speed 2 (£65 billion). Modern government involves large numbers because the economy is so much larger.

It’s worth mentioning at least in passing how this bill was reached. Going back through the records of the debate, there are a number of biting criticisms levelled by abolitionists at the ‘West India interest’, effectively implying that the compensation is far above the income actually lost. It is also worth remembering that the country as a whole generously subsidised these plantations into profitability, leading Adam Smith to describe the colonies as being “to the great body of the people, mere loss instead of profit” — a view later confirmed by economic historians (8).

And this is where we really reach the crux of the matter; whether Britain should have compensated slaveholders. This is not a question about the moral principle of abolishing the institution of slavery, which is entirely clear, but how politicians went about doing it.

Let’s say you’re an abolitionist in Parliament in 1833. Last year the Reform Act finally weakened the West Indian lobby to the point where abolition may now be plausible. Against you, you have a large vested interest that wishes to maintain slavery. As a measure of the political power of the ‘Sugar Interest‘, remember that the viability of the plantations effectively rested on heavy government subsidies in the form of tariffs on competitors, administration, and military protection.

While you feel that “if any persons are entitled to compensation, it is the slaves themselves”, you also know that compensation will probably be a necessary evil if emancipation is to be won; you need the West India lobby to concede, and the Caribbean to comply. The conclusion the abolitionists reached (9) was that this was worth it, even though they may strongly oppose the principle (10). It may even be the case that you have to concede ‘compensation’ far above the actual value of the plantations, and the continuation of forced labour under an ‘apprenticeship’ (11)

None of these things please you. You view them as morally abominable. You speak out against them, but it is also clear that this is the price of compromise in order to abolish slavery today.

Do you take this less than perfect abolition after 18 years of work, or do you keep up the fight until a total victory can be found?

Looking back from the comfort of the 21st century, it’s easy to say that no compensation should have been made; instead of paying, we should simply have mandated release. But that was not the choice that was offered; the question is not “did slave-owners deserve compensation” so much as “should the abolition movement have waited until a complete victory was available”. To me, the answer is very clearly ‘no’ to both (12).

Conflating these questions may partly be why recent journalism has tended to reject nuance. The criticism of the “whiff of self-congratulation” around British slavery is in a way its own national myth, particularly when it focuses on the outrage of “government bailouts” for slave-owners. The option of waiting was there, but the people of the country were willing to pay in order to get abolition done; to wish that things had been otherwise is almost to indicate a preference for a more extended period of suffering so that we can feel better about the moral purity of the way slavery ended.

And here perhaps it’s worth dwelling for a moment on the contribution of the British public to abolition. The profitability of the colonies in the first place was maintained by placing upon the taxpayer the burden of tariffs, defence, and administration necessary to make the plantations viable. When the time came to abolish them, the taxpayer paid again. At that point in time, the government budget was financed largely through indirect taxation (13), which in turn fell disproportionately on the poorer members of society. In other words, the wealthy benefited from slavery, received compensation for its abolition, and throughout it all the poor paid (14).

Image courtesy of Can Pac Swire, used under a Creative Commons Licence.

- Not 1833, see below for more

- Some interest bearing instruments appear to have been issued as a way of smoothing the path of compensation payments but these seem to have been short-term bills

- This raises an interesting philosophical question; at what point in the process of rolling over and repaying debt do we track an individual debt and consider it repaid?

- The idea that the sum was so large it had to be financed by borrowing is also a sort of misconception; if you’re going to make a large one-off payment it’s far better to borrow and pay back than it is to adjust taxes or spending for a single year

- A brief note on the maths here. If you spend a large amount of money on a one-off payment in 1835, if you want to compare it to (say) 1833 then it will inevitably be a much larger share of the budget in that year. This is because you’re comparing a large hypothetical addition to the spending that actually took place.

What the graph in this text does is show what share of the budget abolition would have taken up in a given year when the budget includes the cost of that bill. In other words, in 1835/36 it shows £20 million as a share of that year’s spending, and in every other year it shows £20 million as a share of “that year’s spending plus £20 million”.

The spike/dip over 1835/36 and 1836/37 is probably partly an artefact of this treatment. We’ve assigned all £20 million in spending to 1835/36 but it’s very probable that payments continued into the next period (which begins in January 1837). This means that the first year compares £20 million of abolition spending to a budget that contained less (pushing the share up), and the second compares £20 million of abolition spending to a budget that contains a little more than that (pushing the share down). The other effect we might be seeing is deferring of other government spending from one year to another.

Technically, we should probably also adjust for inflation over this full period and if anyone wants to do that they’re welcome to; there isn’t really a strong trend in prices (some inflationary spells followed by deflationary spells) so I was happy with the nominal estimate

- Other businesses can trace a line back directly to the profits of slavery. Here the argument is a little more complicated, but it’s worth thinking about the counterfactual: the capital that was invested in the slave trade would have been invested elsewhere, and the economic niches would still remain to be filled in an economy which would likely have been slightly larger. Without slavery we might still have Lloyds and Greene King (only funded by trade with North America or putting money into industry), or we’d have rival businesses that look almost identical bar the name.

- Similar calculations that get a figure based on the share of government spending or GDP spent on abolition fall into a related trap; the government is responsible for far more today, and we produce significantly more. It is not really intuitive to me that the discovery (for instance) of nuclear power or the internet means that we should inflate the amount spend on abolition to a greater degree.

- The idea that slavery is highly profitable is one that’s intuitive but probably wrong. The slave is forced to work without pay, but the slaver is handsomely paid. As McCloskey and Thomas describe it, the profits were “passed back along the line of dealers in men and reached the original source – the enslaver”. This was usually a member of a different society in Africa.

- As eloquently stated by Fowell Buxton: “I am quite ready, and so are the people of England, to give the planters [£20m] if it will secure complete emancipation to the slaves; but certainly not otherwise.”

- O’Connell: “The Right Honourable Gentleman asked whether it was just that you should take the slaves from the planters, without any remuneration? What right had they to make the negroes slaves? What right have they to continue them slaves? Talk of justice — talk of fair dealing — when you propose to treat the negroes in this way… it does not justify you in keeping the negro in bondage: you have no case against him. There have been two parties to the iniquity– the British planter on the one hand, and the British Government on the other. The negroes are the victims of your cupidity. You now call upon the negroes to undergo twelve years of suffering; and, in the same breath, you talk of liberty existing in every part of the British dominions. You proclaim the utter and entire abolition of slavery, and yet you retain slavery under another name, for the space of twelve years… he is now compelled to work by the terror of the whip before his eyes: you, however, take away this, and have him removed to a distance to be flogged. It is a puerile delusion to call this emancipating the slaves.”

- Going back to Fowell Buxton, “The Right Honourable Gentleman proposes that the slave shall work for twelve years as an apprentice to his master, without receiving any wages. Now I maintain that such a provision is a direct invasion of all the principles of equity and justice, and a downright robbery… again I ask, will the people of England pay [£20m] that all the horrors of slavery may be continued?”.

- Fowell Buxton, in the end, voted for compensation “as giving the best chance and the fairest prospect of a peaceful termination of slavery”, but wanted half the sum held back until true freedom was attained — an amendment that was rejected

- Indirect taxation accounted for ~70% of all government revenue. For a free journal making broadly this point in a less helpful way see here

- For a broader discussion of this point in the context of empire, read McCloskey’s chapter