This follow-up to my previous blog post goes into more detail on the UK approach to tackling the coronavirus outbreak, the assumptions driving it, and the alternative policy measures available. The usual disclaimer applies; I am trying to pull together information so I can get the shape of this in my head. Any errors are my own responsibility.

(1) The UK government’s plan

(a) The plan does appear to be developing herd immunity.

Three days ago we had Peston telling us the strategy is “to allow the virus to pass through the entire population so we acquire herd immunity, but at a much delayed speed… such that the health service is not overwhelmed and crushed”.

This was in line with junior minister Lord Bethell’s statement in the House of Lords, where he noted that “creating some kind of herd immunity… is clearly the objective — well, not the objective; rather, it is one of the results of the virus passing through… so herd immunity will actually provide resistance to future visits by the virus.”

It was also in line with the chief scientific officer, who told the world that “our aim is to try to reduce the peak, broaden the peak, not suppress it completely; also, because the vast majority of people get a mild illness, to build up some kind of herd immunity”.

Following the somewhat heated reaction to the revelation that the government intends to allow at least 60% of the population to be infected with a potentially deadly disease with unknown long-term health outcomes, there has been a degree of walking back from such blunt statements, with Matt Hancock wheeled out to tell the public that herd immunity is not the plan.

Adam Kucharski presents a reasonable case for the defence on Twitter, explaining that herd immunity “has never been the outright aim” so much as “a tragic consequence” of a virus that will not be fully controllable; if you can’t control it, you’ll get it, so it’s about managing the timing with which it arrives.

This is probably fair; whether or not herd immunity is ‘the aim’ is a matter of splitting hairs. It is more the case that the government does not believe the virus can be stopped, so that herd immunity is how this will end. The major differences between the government and its critics are on how, given the assumptions underlying this view, we might best manage the flow of cases, and on whether the assumptions hold.

(b) The initial policy measures announced were very slim, and did not appear to reflect mechanisms for spread.

The early British response effectively consisted of asking people to wash their hands to avoid falling ill. If that fails, people developing a persistent cough or temperature were encouraged to remain at home for a period of seven days.

This was — as with much of the British strategy — out of step with the rest of the world, where an isolation period of two weeks is recommended. While patients may only be contagious for ten days or so, a two week period is simple and sure.

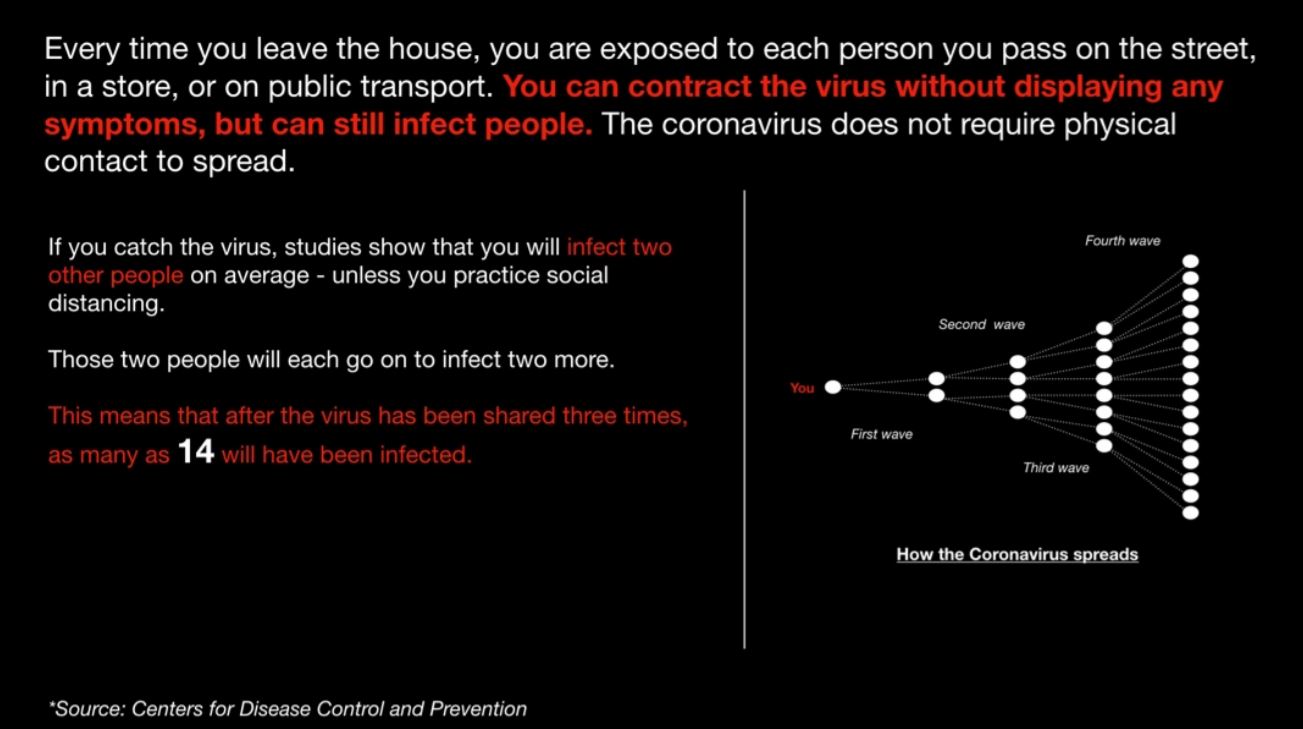

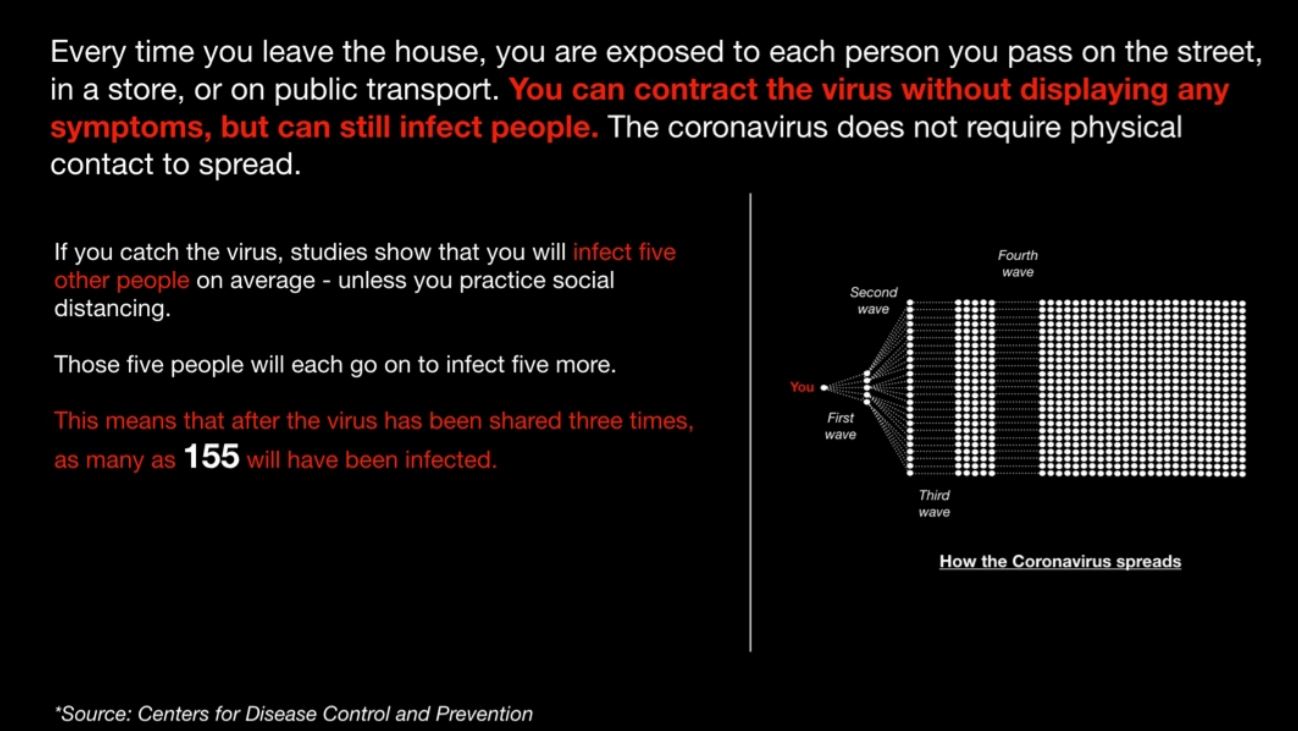

The virus appears to have an incubation period of approximately 5 days before symptoms appear. Patients are still contagious during this period, with a study finding that roughly 50% of patients in one studied group and 60% of another transmitted the virus to another person before showing symptoms. A pre-review paper suggests that up to a quarter of infections generated by a person may result from this phase. Moreover, a substantial share of infected individuals may remain asymptomatic throughout their experience.

This suggests that those living with self-isolating individuals are likely to catch the disease and transmit it in the period before they themselves develop symptoms sufficiently worrying to cause them to enter isolation.

Focusing purely on patients who are currently symptomatic will therefore miss a large number of carriers, and will be of limited efficacy in slowing the growth of the virus. It is not clear whether the modelling assumptions that generated the government’s understanding of the efficacy of different measures accounted for this.

It is worth noting that there is research suggesting that self-isolation may fail to have the anticipated effect when asymptomatic transmission is possible.

(c) Delaying delay.

Beyond this initial response, the government anticipated installing sterner measures over the following month. Concerns about ‘social fatigue’ led the government to choose this timetable; people would comply with social measures for a time, before changing their behaviour — potentially raising infection rates again at the peak of the disease.

From the government’s point of view, this reduces the policy response to a matter of timing; you get to introduce restrictions once, and then their effect decays. The game is to introduce them at the point where they will have the largest possible impact on the peak NHS caseload. Hence Robert Peston’s “senior government source” stating that the government is “waiting for the optimal time to force restrictions on our way of life that will be very painful”.

This is a very different perspective from that given if you believe that restrictions can be made to work long term, as Hong Kong, Singapore, and China appear to. In that framework, once the disease arrives you commit to rooting it out as early as possible; the nature of exponential growth means that a reduction in the rate of growth has a correspondingly larger effect the earlier it is introduced.

This raises an interesting possibility; if containment elsewhere does prove successful, and the UK approach results in the disease becoming endemic — or at the least, uncontained — then we may find ourselves facing travel restrictions when looking to leave these islands.

(d) Not met with universal acclaim.

As I’ve said before the UK response is very much out of line with that of other countries, and there is hardly a solid consensus behind it here. As Birmingham’s Professor Alan McNally says, “social distancing has worked in China, Singapore, and other countries”, while the Lancet’s editor-in-chief describes the British approach as “playing roulette with the public”. As covered later, the assumptions underlying it have also been questioned.

Others not specifically responding to the UK policy approach have made comments that clarify just how unusual it is, with the WHO director general telling the world that the requisite policy mix was “Not testing alone. Not contact tracing alone. Not quarantine alone. Not social distancing alone. Do it all.”

In the American context, Susan Rice — in addition to noting the time a containment strategy focused on keeping out certain groups of travellers might have bought — called “aggressive social distancing” the “last key tool for slowing the spread of the coronavirus in the United States”. Without it, there was very little hope of flattening the curve sufficiently.

(e) High Risk

This last comment points to one of the biggest flaws in the government approach. If it works, fantastic. But if it fails, it will all but ensure that no plan b is viable; infection will be widespread and growing fast, and hospitals will be ensured of a period of intolerable strain.

In order to pull it off, the government will need every assumption to hold. And it will need to time its interventions all but perfectly (or at least err on the side of moving too soon rather than too late) — something that could prove challenging without sufficient testing capacity to monitor the spread of the virus through the country.

From this perspective, it is worth noting that even a perfect application of the strategy could see the hospital caseload peak well above capacity.

(f) This plan has changed, partly because the government has been caught off-guard by assumptions failing to hold.

Since the initial steps outlined above, the government has begun to backtrack. There is now a wealth of contradictory information available.

Robert Peston, the closest to thing to a government spokesman currently available, has set out a list of potential measures in The Spectator. These include asking the over 70s to remain in strict isolation for a period of four months (likely to be enforced within the next 20 days), banning mass gatherings (over the next weekend), and temporarily closing pubs, bars, and restaurants some time after that. The option of temporarily closing schools to the children of those who are not “key workers in the NHS and police” is also being considered.

Matt Hancock, meanwhile, is telling the world that “We have a plan” and that “Herd immunity is not a part of it”. Except, as covered above, it very clearly is. His description of the government’s approach as possessing “maximum transparency” could itself be somewhat more transparent.

There are three possible explanations for this shift in tone and rhetoric. The first is that the government more clearly wants to communicate the policy set out in (1a). The second is that there has been a genuine shift generated by a desire to be seen to be acting in-line with the public mood; retaining confidence is essential in generating behavioural change. Even if policies are not being introduced earlier than planned, greater transparency could set minds at ease and win over approval, as well as emphasising how seriously the government is taking matters.

The third and least optimistic is that the assumptions underlying the policy are already being shown not to hold, and on this note it is probably relevant that the Times has been reporting that the virus has been spreading faster than government models predicted.

Conclusions

i) The plan, such as it is, is to try and control the spread of the virus through the population rather than attempt to contain it

ii) The measures adopted to do so (so far) may not achieve this, as they could potentially allow for significant spread

iii) More effective measures may be put in place down the line. It is unclear whether they will be timed correctly.

iv) Other countries are still attempting containment, or are attempting a similar controlled spread using dramatically more stringent tools.

v) It is not clear that this strategy will allow for an effective plan b. It is very reliant on assumptions holding.

vi) It is possible that the plan is already changing, reflecting either a need to retain the confidence of the public, or the early warning signs that needed assumptions will not hold.

(2) What assumptions underlie the government’s approach?

(a) The virus will continue to be a threat for the foreseeable future.

Public Health England believes the coronavirus outbreak could last until spring 2021. There will be no vaccine within a year, with a less than 50% chance of one being developed in this period. Containment within the UK — to the point where the disease dies out — will not be possible, and even if it were it is very likely that the disease would be reintroduced from overseas.

(b) The virus is likely to display multiple peaks when we would prefer one

The prospect of a double peaked outbreak underlies much of the UK’s planning. There are, as far as I can tell, three components to this logic. The first is the lower slack NHS capacity in the winter under usual circumstances; as seasonal influenza hospitalises the elderly, fewer beds will be available to treat coronavirus patients, and comorbidities are likely to occur which will reduce patients chances of surviving.

The second is that a number of viruses find winter conditions considerably more suitable for reproduction. It is possible that the coronavirus will spread more rapidly in the latter part of the year. Moving patients from the ‘unexposed’ to ‘immune’ shares of the population over the summer is vital in preventing a dramatic rise in cases in the winter.

The third is the expectation that behavioural changes might naturally drive a multiple peaked pattern of infections, as with the 1918 flu pandemic.

Of these, the second and third points are most questionable. Behaviour depends on beliefs and incentives, which may be very different in the more connected world we live in, while the reason why some diseases display seasonal patterns is unclear making it hard to infer whether the coronavirus will do so.

There are some suggestions that an environment with greater absolute humidity provides certain viruses with greater viability. It is possible that coronavirus will be one of the viruses which benefits, but there does not appear to be sufficient information to say with any certainty whether it is. It is worth noting that the virus has sustained transmission in supposedly hostile environments. As Harvard epidemiologist William Hanage notes, flu rules might not apply. Exposing people to the disease now to avoid a hypothetical second peak is risky.

(c) Social fatigue/Isolation fatigue/reduced compliance/disobedience

The assumption underlying the delay in harsher messages was simple: people would only change their behaviour for so long, went the logic. When instituting a new plan, you would therefore have a window of obedience before people began to change again — potentially just a few weeks, with any change in behaviour arriving at the peak of the crisis. Ask less now, get more later. Avoid “self-isolation fatigue”. But what precisely was this based on?

Over the last few days the Guardian managed to get a member of the advisory group on record pointing towards two relevant bits of evidence. The first was “a rapid review published in the Lancet last month on the psychological impact of quarantine”, which listed some potential negative psychological effects upon those undergoing it, emphasised the limitations of the papers reviewed, and recommended keeping such measures in place for as short a period as possible. The second was “a paper by the Economic and Social Research Institute in Dublin on how to harness behavioural science to fight the coronavirus”, which found that “extending isolation periods beyond initial suggestions risked demoralising people and increasing noncompliance”. The same paper also noted the danger of highlighting the potential negatives of isolation in advance, as people might understandably try to avoid such measures.

Spot the problem? Neither of them make the case for delaying the introduction of measures; they say to keep them to shorter periods if possible, and to be clear about how long they will last. The evidence base for the fatigue effects is not clearly visible in the literature.

This is all the more confusing when we consider the November 2018 update on pandemic modelling, which noted that “all social distance measures depend on compliance by the population which, in turn, depends on the social acceptability of the measures. Without good behavioural research on these it is difficult to predict the impact of such measures being deployed in a future pandemic”. Quite how we moved from a situation where fatigue was a total unknown to an agenda-setting fact is something of a mystery.

Perhaps more importantly, the research the government does have emphasises the need for transparency and good information in alleviating concern — something we are sorely lacking.

Other research has, for example, found that believing an outbreak has been exaggerated or having lower information understandably reduced engagement with social distancing in previous outbreaks. What message does the government believe ‘business as usual’ will send?

Similarly, while a UCL review of behaviour in previous outbreaks found that at-risk groups were more likely to comply with protective behaviours, a high level of trust in authorities was also important. Given the very conspicuous doubts over the government’s approach, could it be possible that attempting to over-optimise the timing of interventions may be reducing their efficacy through other channels?

A relatively recent paper examining willingness to self-isolate found ‘attitude’ (towards self-isolation) and ‘social norms’ (public perception of actions) played the largest role in regulating behaviour; what effect do we think telling people they are expected to break quarantine, can’t be trusted to behave sensibly, and indeed don’t need to take significant actions might have on agent beliefs and actions?

Research in an Australian context suggests that creating credible concern over personal or familial wellbeing would be associated with improved adherence to public health measures. Telling the public that everyone will get it, and all will be well, seems likely to work against this effect.

It is worth noting that questioning the efficacy of measures is consistently found to be an effective way to undermine cooperation. Legitimate, competent authority, normalising desirable behaviours (and creating strong norms against what we might term ‘selfish’ behaviour), and effective communication are all tools through which we can increase compliance with measures.

On which note, there is research suggesting that one major factor causing people to end self-isolation early is not fatigue or boredom, but simply money. The best way to improve the efficacy of social-distancing measures is to ensure people can afford them.

I have thrown a lot of papers at you here. As you can probably guess, I can’t vouch for the design and statistical power of each one. My point is that the government has placed a great deal of weight on a single assumption that may not hold.

It is unclear, for instance, why people would become bored with quarantine and leave home at the peak of the crisis, or continue to do so if their actions caused the rate of infections and deaths to spike upwards once more. It is also unclear whether the concern of non-compliance with voluntary measures is significantly reduced when such actions are imposed in top-down fashion.

It is also unclear whether the current behaviour of the British public lends support to one side of the argument or the other. On the one hand, you have people like Michael Head, an academic at Southampton, who suggests that “People already can’t be trusted to buy toilet roll properly, so how about long-term compliance when significant levels of freedom are removed and there’s a need to stay indoors for long periods of time? The evidence, as we have it right now, suggests it will decline.”

On the other, editor-in-chief of the Lancet Richard Horton notes “the public acted to socially distance, avoid mass gatherings, and work remotely ahead of govt advice”.

The distinction between the two is partly based in a misunderstanding of incentives; while only one is socially desirable, both reflect a strong perceived incentive to take actions to preserve personal and familial welfare — a perception that could potentially be harnessed for the better.

That the assumption of fatigue is at best questionable has been borne out by the response of the behavioural science community at large; an open letter signed by 481 individuals (at the time of writing) in the field of behavioural science expresses concerns that the assumption of “behavioural fatigue” is insufficiently based in evidence, ignores the possibility of radical behaviour change of the sort seen in South Korea, and that the approach of “carrying on as normal” may undercut the required urgency of action when government advice changes.

(d) Building up long term immunity to the virus is possible

In order for “herd immunity” to build up in a population, it must be possible for exposed individuals to develop immunity in the first place. There have been some suggestions that individuals have been reinfected after recovering from the virus, but it is not clear at all that this is common or even anything other than an artefact of inaccurate testing.

The larger question is how long such immunity would last. As the British Society for Immunology has said, “Because [the virus] is so new, we do not yet know how long any protection generated through infection will last. Some other viruses in the Coronavirus family, such as those that cause common colds, tend to induce immunity that is relatively short lived, at around three months.”

(e) Timing interventions is possible

Note that given our low testing capacity this may be difficult.

(f) We have enough capacity to manage the peak caseload generated by this approach, and can get away with an attempt to “flatten the curve” short of the measures imposed elsewhere.

Fair warning, this one is dark.

The core assumption used by the government is that without measures the NHS will collapse, as we have seen elsewhere. Every measure taken by the government is taken with the aim of avoiding that.

The problem with this is that the government’s intended strategy still implies a considerable peak caseload relative to the number of beds available. Up to 7.9 million people may require hospitalisation according to Public Health England, with an extant supply of 170,000 hospital beds (~4,500 critical care beds). There are already “growing reports of problems on the ground”, with bits of the NHS “already falling over”, and staff exposed to the disease. As I said in my previous post, the mathematics is not optimistic.

A team of American public health specialists have gone somewhat further. Even among the seemingly healthy, there will be deaths as a consequence of the herd immunity strategy; immunisation by infection is considerably less safe than immunisation by vaccine.

The real risk however is the potential explosion of cases under the light touch measures envisaged by the government. The Americans note that even using more conservative (favourable) estimates than those adopted by the UK government, 20-40 year olds alone will require up to twice as many intensive care beds than are available. With older groups even more exposed, it’s not hard to see why they chose the paper’s optimistic title: “The direction of the UK Government strategy on the COVID-19 pandemic must change immediately to prevent catastrophe”.

One of the authors of the paper, Professor William Hanage, believes that “strong social distancing” will be required to do so, with measures (discussed below) including encouraging working from home and providing financial support for those doing so.

(g) An alternative framework is available.

As Anthony Costello notes, other countries have adopted a very different strategy. The approach in China, in particular, has been to crack down on pockets of infection: people are tested, contacts are traced, family clusters are identified, and individuals are isolated. Other countries, such as South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan, have adopted less extreme versions of this strategy.

They will all face, as the UK has been keen to point out, the issue of how to unwind infected areas. But relative to a disease spreading freely through the population this seems like a good problem to have. If people are likely to vary their behaviour to become more risky as cases drop, and then less risky as they rise, then the caseload will oscillate in a manageable fashion.

Ultimately, taking strong measures gives a government far greater control over the speed of infection than those indicated by the UK approach. By varying social distancing it would be possible to pursue a policy of herd immunity over a more extended period, or to hold the disease in check for the twelve to eighteen months that a vaccine might take. The approach will place more strain on social organisation, but less on healthcare. It seems worth considering.

Conclusions

i) The coronavirus outbreak is likely to last for an extended period, and total containment in the sense of ‘eradication’ is not possible.

ii) It is possible that the virus could display multiple peaks in cases. This is however uncertain, and basing a strategy around the hypothetical poses its own risks.

iii) The evidence for social fatigue is threadbare at best, and we could likely implement longer term measures as used elsewhere. It certainly does not suggest delaying action.

iv) It is not clear whether building up long term immunity is possible

v) It is not clear that we will be able to time measures correctly.

vi) It is not clear that the measures proposed by the government would ‘flatten the peak’ sufficiently when implemented.

vii) Alternative frameworks for action are available.

(4) Things we can do

(a) Communicate better.

I don’t think it’s too strong an ask for the public to learn about massive changes to their way of living from official, named government sources with context, information, evidence, and offers of assistance, rather than through Robert Peston’s blog.

This is really, really basic stuff. The section above covered the importance of credible and authoritative messengers in generating desired changes in behaviour, and the section above that demonstrated the confusion the government’s current stance has left us in. Secrecy and spin might be the substance of politics, but it’s poorly suited to the task of gearing a nation up for the task of fighting a pandemic.

If I were to lay out the principles for an alternative system, I would choose the following:

(i) Being open and transparent;

(ii) Using clear and simple communications;

(iii) Acknowledging the existence of uncertainty;

(iv) Using absolute, as well as relative, risk;

(v) Framing ambiguous messages negatively [e.g., 1 in 100 will be ill, rather than 99 in 100 will not]*;

(vi) Using visual aids wherever possible.

*This principle recently broken by Chris Whitty.

These principles seem sensible to me, but more importantly they’re the ones the government set out in its scientific summary of evidence for pandemic response planning. It should consider following them.

(b) Make it easy to follow the rules, including providing fiscal support to individuals and firms.

The best way to ensure compliance with the rules is to make them easy to follow. Even medical workers will find multiple rules tricky to follow, reducing the probability of compliance as the work required increases. Fewer large rules may be more effective than an array of smaller ones, and stating the rules simply is likely to help.

As noted above, fiscal ability is a major constraint on people’s ability to stick to regimes requiring them to withdraw from economic activity. As Greg Mankiw says, “Fiscal policymakers should focus not on aggregate demand but on social insurance. Financial planners tell people to have six months of living expenses in an emergency fund. Sadly, many people do not. Considering the difficulty of identifying the truly needy and the problems inherent in trying to do so, sending every American a $1000 check asap would be a good start. A payroll tax cut makes little sense in this circumstance, because it does nothing for those who can’t work.”

These are pretty much the textbook circumstances under which running a fiscal deficit is acceptable.

As Steven Hamilton writes over at The Bulwark (and if you have any interest in economics you should read this piece), any package should not only target vulnerable households. If we want to emerge on the other side with the minimum possible damage, businesses which would otherwise have been viable should be given support to bridge the gap in revenues. The alternative would be “a surefire recipe for a long and painful recession”.

Providing support to businesses can come alongside measures such as mandating sick leave and subsidising home working; there is no need for an unconditional transfer of money. By combining the two we will hopefully be able to improve compliance with measures taken to reduce the spread of the virus, while ensuring that we don’t set ourselves up for a painful recovery.

(c) Test widely.

As the 2018 Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Modelling said, “It is important to ensure mechanisms are in place to measure rates of infection in the community at different stages of the pandemic”.

This is not influenza, but it is a pandemic. Perhaps due to limited capacity the government appears to be giving up on community testing, reserving such capacity as is available for the most vulnerable.

Given the stated desire to time interventions for maximum impact, the aim of acquiring mass immunity, and the potential demand for localised measures to prevent regional health system collapses, it seems unwise to measure the flow of cases by the number arriving in hospital — particularly given the potential lag between infection and hospitalisation.

(d) Consider carefully the evidence on behaviour.

Rather than using the somewhat nebulous notion of fatigue as a reason to avoid action, the government could consider looking at the research on the interaction of behaviour and policies. Creating social norms that encourage social distancing (such as emphasising taking sick leave or working from home as the right and unselfish thing to do), maintaining public trust in the efficacy of measures and the strategy adopted by government to ensure continuity of supply and public safety (ensuring they understand what is required, and reducing less desired behaviour such as hoarding), and ensuring that people understand the level of threat posed to themselves and their families could all work to improve compliance.

If nothing else, switching messages while doing nothing may not maintain confidence in plans.

(e) Implement marginal social distancing policies.

There are easy marginal gains on the table. For many people, working from home — at a reduced level of productivity — is an option. As Hanage says, anyone who can do so should. For a disease which is contagious in asymptomatic people, this additional space could help limit spread. While the broad evidence is that the effect is limited, where this is already possible it seems likely that the cost will be outweighed by the gain. Perhaps more importantly, it would create room to consider policies on school closures.

For a disease with no background immunity, the government’s pandemic flu research suggests school closures could reduce the peak by up to 50%, and the total number of cases by 10-20%. The latest modelling figures for the coronavirus suggest a 14 week closure would reduce the peak caseload by 10-15%. Given the role of young children in this epidemic as largely asymptomatic spreaders, this seems like a useful potential outcome. If mitigation is the aim — as is currently the case — then reactive closures upon a case arriving for a period of three weeks would produce roughly the same effect.

Closing schools changes behaviour. It is possible that it will do so in ways that will work against the effect we hope to achieve; as David Halpern says, “The models rest heavily on what people will do. Will people comply with instructions, and to what extent? If kids don’t go to school, what will happen?”

With that in mind, it is still worth noting that many of the alternatives are preferable. If children end up in a daycare — undesirable — it is still likely to bring together fewer than a school of several hundred, with associated limits on the spread of infection. If they are likely to be looked after by grandparents, efforts should be made to dissuade this and explain why it is to be viewed as undesirable.

If key workers — not just in healthcare, but in energy, transport, security, and so on — are unable to find childcare, then the option of limiting access to schools to only the children of those parents who cannot work from home or find alternative arrangements is open to us. It should not be impossible for a state that hopes to manage the peak of an epidemic to sort out a rough and ready solution to the childcare needs of NHS workers.

For limiting large scale events, evidence is limited, although the government estimates a direct reduction in cases of 5%. However, it is worth noting that from a psychological standpoint alone it would emphasise the need to change patterns of behaviour in order to limit exposure to the virus.

(f) Back up policies with enforcement.

This should go without saying, but relying on voluntary cooperation for all measures is a non-starter. The government should be willing to add some stick to the incentives for compliance.

(g) Cut the red-tape.

The American response has been hamstrung in part by CDC restrictions on testing, and a refusal to use the German-made kits supplied by the WHO. In Britain, we are eyeing the possibility of drafting in final year medical school students to help provide necessary manpower.

Where otherwise sensible restrictions can be removed in a way that will not endanger patient safety to a greater degree than inaction, governments (including ours) should be looking to clear the way. Providing care worse than that provided by a fully trained doctor is better than providing no care at all.

(h) Desynchronise if possible

This penultimate thought is my own, so I suspect it will make less sense than the rest. As I understand it, the USA is currently making a hash of its response to the virus, while the UK is attempting to deliberately target a peak of cases in the summer.

This strikes me as suboptimal for the following reason: if we experience our peak outbreak at the same time as somewhere else, we are likely to be competing for resources produced by stretched global supply chains. If we can desynchronise our pattern of infections from that of our American and continental cousins, then we may be in a better position to fight the disease.

Over the longer term, this suggests that countries might wish to coordinate when loosening restrictions on behaviour in order to avoid simultaneous flare-ups.

(i) Remember healthcare workers are human.

We are likely to be asking an awful lot of NHS staff in the coming year. It is possible that alongside sickness absences, some healthcare workers may be unwilling to come in at all. Arranging childcare, paying for hours actually worked, ensuring the supply of personal protective equipment, and taking steps to reduce stress should help to limit lost hours.

Conclusions

i) The government needs a clear and unambiguous message on strategy and measures taken.

ii) The government should make it easy for households to follow its requests both in what it asks of them, and through financial support.

iii) If your policy is dependent on timing, widespread testing seems important.

iv) Rather than pointing to ‘fatigue’ as a catch-all excuse for delaying action, the government should consider the behavioural consequences of action and inaction carefully.

v) Implementing marginal social distancing policies should be on the table. These may be necessary to enact the government’s current strategy.

vi) Relying on voluntary compliance with measures may be unwise.

vii) If policies designed to ensure safe treatment in normal circumstances are preventing treatment at all, the government should consider temporarily loosening them. The range of outcomes is sufficiently changed that they may do more harm than good.

viii) If possible, when timing the peak of infections the government should probably avoid coinciding with other nations, or at least staggering regions across the UK.

ix) Healthcare workers are human and will require additional support.

(5) Summary

God, that was long.

It is not at all clear that the assumptions behind the government’s plan are holding. Given that, more aggressive social distancing measures will probably be needed, among other policy measures. Accounting for the speed with which this virus spreads, putting these into operation sooner rather than later would be desirable.

Header image courtesy of Sanofi Pasteur on Flickr, taken by CDC/ F. A. Murphy, used under a creative commons license.